BROCKENHURST HOSPITAL.

Published in the Press, Volume LV, Issue 16561, 28 June 1919

BROCKENHURST HOSPITAL. A MEMORIAL OF THE NEW ZEALANDERS.

A correspondent, M.D, writes:-

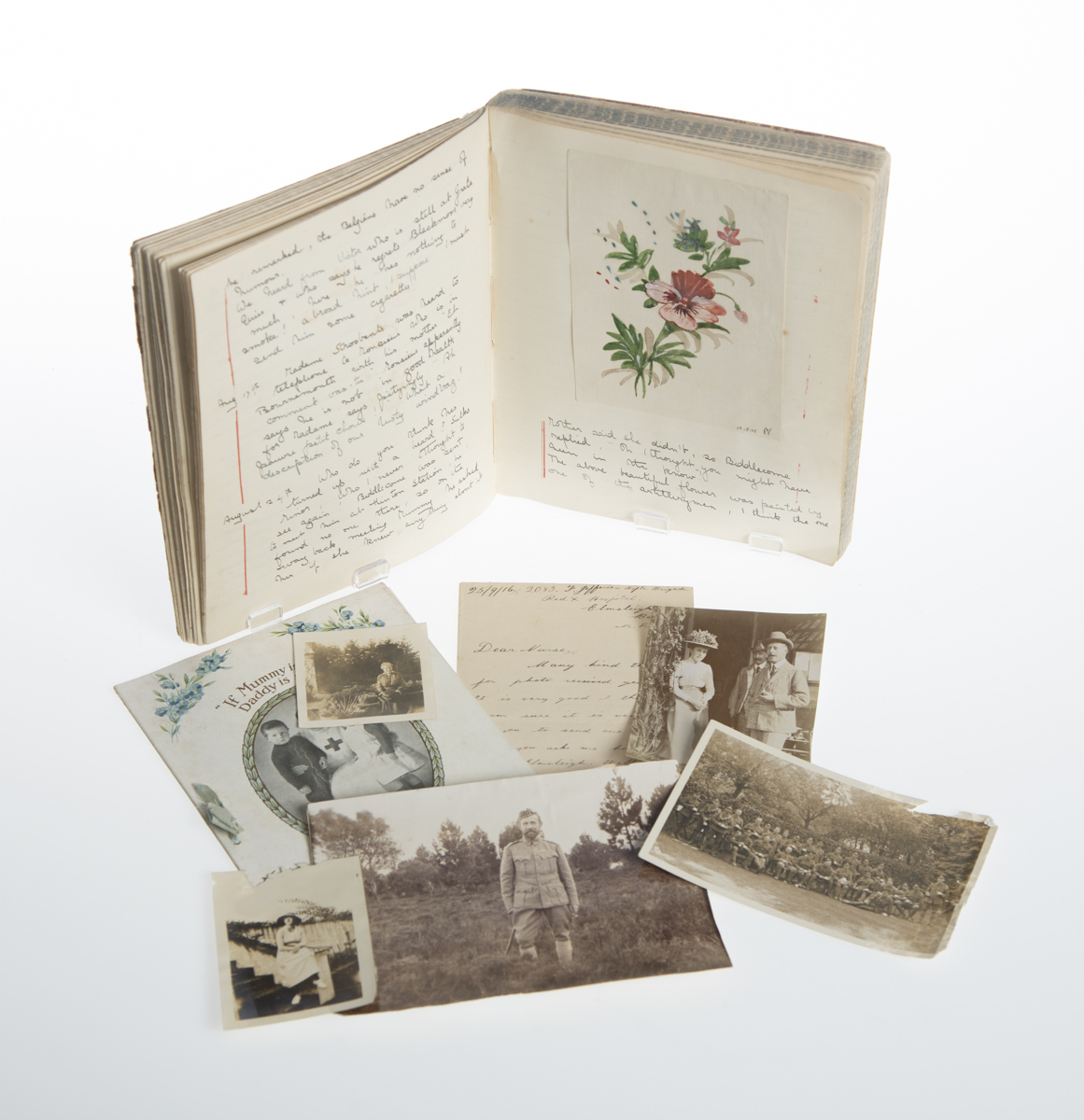

Last February the demobilisation of the New Zealand No. 1 General Hospital at Brockenhurst, Hampshire, took place. An English lady, formerly resident in Christchurch, has just sent me a detailed account from the local parish magazine of the official and interesting ceremony in connection with the presentation of a New Zealand flag, in gratitude for the continuous kindness of the residents and as a memorial of the long New Zealand occupation of Brockenhurst.

I visited this charming locality in August, 1917. It lies within the New Forest, and is of great antiquity, being a genuine old forest village. These famous woodlands are at least a thousand years old, the term New as applied to them being a misnomer. It has been proved by modern research that William the Conqueror did not in all probability plant a single tree, as it was known in Saxon times as “a mickle deer frith.”

The Church of St. Nicholas stands on a hill approached by a winding, leafy road banked by luxuriant wayside bracken, and shaded by noble trees; green pastures lie gleaming beyond. The churchyard is a truly sylvan Garden of God, placed on the sloping hill-side, and now known far and wide as the last resting-place of the New Zealanders who died at Brockenhurst Hospital. At the time of my visit, less than two years ago, there were, thirty-five of these graves. Alas, there are now over ninety! The church authorities reserved a largo space in one portion of the grounds, and there on the sunny slopes amid a veritable garden of flowers, intermingled with stately trees, one a very ancient and magnificent yew, our brave, departed lie in sylvan holy peace.

Heavy rain fell during my visit, but did not deter me from paying a silent tribute of respect to the heroic dead nor from taking a then full list of their names. Over each grave a Wooden cross was erected bearing the name, rank, company, and date of death. Few from these shores who visit England in future but will make this pious pilgrimage. Many of us have since heard and read of the touching letter from a Brockenhurst lady to Colonel Fenwick the New Zealand general commanding officer of the hospital, assuring that those graves should always he cared for and tended by loving hands. Their graves and their memories will always be green.

There are many sad-hearted parents who may be comforted by knowing something more of this sweet country churchyard where their dear ones lie amid trees and flowers, green pastures, and rural peace, as well as of the warm-hearted sympathy and attention which enfolds them for all time. The extract referred to is as follows: New Zealand No. 1 General Hospital.—The demobilisation of this great hospital is- now practically complete.” The two large hotels and the numerous houses occupied by nurses and staff are gradually being restored, to their owners, and the vast collection of iron buildings, known as “Tin Town,” is now emptied of all its “blue boys,” and will have to be disposed of by sale.

Before the last batch of men departed, on Wednesday, February 19th, at noon, a picturesque ceremony took place. The New Zealanders presented a-beautiful silken flag of their Dominion to be hung in the parish church as a memorial of their protracted sojourn in Brockenhurst. The vicar and churchwardens, to whose custody it was entrusted, stood at the church yard gates, where they received the flag from the officers, nurses and a large company of New Zealand soldiers, who were drawn up on the green outside. A large number of parishioners were present. A band was in attendance, and also a cinematograph, which managed to produce some most successful films in spite of a continuous rain. The films were subsequently exhibited at the hospital, and have now gone to New Zealand. Where they will be shown everywhere as an evidence of the lasting goodwill and friendship between Brockenhurst and New Zealand. The flag now hangs over the chancel arch as a similar evidence here. The following letter, suitably typed and framed, which now hangs in the tower porch, will be read with interest:

Letter from Col. Clennell Fenwick, C.M.G., Officer Commanding No. 1 N.Z. General Hospital, Brockenhurst. To the Rev. C. Hope Gill, Vicar of Brockenhurst.

Sir, Before leaving Brockenhurst, the New Zealanders are anxious to make some memorial of their stay in the neighbourhood. We have been stationed here since 1916 and during this period 21,000 New Zealand soldiers have been nursed in our hospital. Our sick and wounded have received great kindness and hospitality from the residents of Brockenhurst, and we wish to expirees our grateful thanks to our friends here. Furthermore, we cannot forget that nearly 100 of our comrades have been laid to rest in the shadow of your beautiful church. We therefore ask that you will permit the flag of our Dominion to hang in your church, to remind the people of Brockenhurst of the gratitude of their New Zealand cousins, and to be an honourable memorial to those who came from the other side of the world to die for all that in nearest and dearest to the British Empire.

I am yours faithfully.

P. CLENNELL FENWICK, Colonel.

You can find out more about the activities, sites and stories associated with the hospital by clicking here: No.1 New Zealand General Hospital