Historic Ordnance Survey maps from the second half of the 19th century show a number of rifle ranges scattered about the New Forest. It is still possible to see visible traces of these ranges surviving at Long Bottom, Burley, Lyndhurst and Brockenhurst.

The ranges at Lyndhurst, Burley and Brockenhurst appear on the 1870 historic OS maps and form part of Napoleonic activity in the New Forest and it was believed that Long Bottom was part of the same period of activity. However it doesn’t appear on historic Ordnance Survey mapping until 1895. The range at Long Bottom was first proposed in July 1894, when Colonel Vandeleur made an application for leave to erect a rifle range, to be used by the ‘Fordingbridge and Godshill Company of the 4th Volunteer Batallion Hampshire Regiment’, at Longbottom near Fordingbridge [Western Gazette, page 7, 20.07.1894]. Local resistance to the project led to initial delays, but newspaper references [Salisbury & Winchester Journal, 15.06.1895] show that the range was in use the following year.

The range at Long Bottom was first proposed in July 1894, when Colonel Vandeleur made an application for leave to erect a rifle range, to be used by the ‘Fordingbridge and Godshill Company of the 4th Volunteer Batallion Hampshire Regiment’, at Longbottom near Fordingbridge [Western Gazette, page 7, 20.07.1894]. Local resistance to the project led to initial delays, but newspaper references [Salisbury & Winchester Journal, 15.06.1895] show that the range was in use the following year.

The range at Long Bottom just below Ashley Walk with 8 firing off points positioned every 100 yards towards two targets along with structures for the magazine and markers hut.

Today visiting the site it is still possible to see the firing off points, the concrete target shelter and a brick structure built into the side of the hill originally believed to be the markers hut.

The following research by Bill Flentje questions whether the surviving structure is the Markers Hut or the Magazine and considers the range in more detail comparing it with other ranges around the country rather than just Brockenhurst and Lyndhurst and makes very interesting reading.

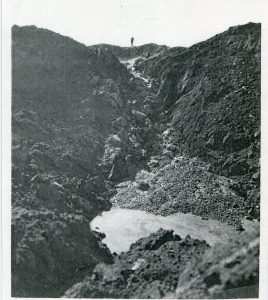

The 1898 map, surveyed 1895, shows the range with its original structures, as built that year. These include a ‘Magazine’ next to a ‘Marker’s Hut’. When visiting the range some 10 years ago, I saw no evidence of the ‘Marker’s Hut’, but I did examine the surviving brick arch entrance to what I believe to have been the ‘Magazine’. (Note: the term ‘Marker’s Hut’ in a ‘rifle range context’ normally describes a small shelter [or ‘mantlet’], solely used in connection with iron targets. A ‘Marker’s Hut’ would be erected either next to an iron target [disc marking system] or some 15 yards in front of an iron target, next to the line of fire [dummy target or flag marking systems]. The ‘Marker’s Hut’ would have given protection to the ‘marker’, who would have monitored the fall of shot on the iron target and indicated to the shooter the value and position of each shot). The 1898 map shows two things, firstly, that no iron targets were in use in connection with the Longbottom range. Iron targets were by now considered unsafe in connection with the use of the new .303” cal magazine rifle. Secondly, the ‘Marker’s Hut’ shown on the map was located some 100 yards from the targets. At that distance, the marker would not have been able to see and identify any bullet hit on the target. For these reasons I assume that the cartographer’s use of the term ‘Marker’s Hut’ in this instance is a misnomer – the structure was simply a troop shelter and target store, which was demolished many years ago. What has survived, however, is the ‘Magazine’ and I attach a photo and map of a similar structure, built into the side of the stop butt (backstop) of a rifle range near Worksop in Nottinghamshire. This allows a meaningful comparison with the structure at Long Bottom.

Official W.O. Rifle Range Returns of 1903, list the range as ‘Longbottom’ <S60> [Southern District No. 60] with 4 canvas targets and firing points back to 800 yards. However, the 1898 and 1909 maps show that only 2 target frames were installed, almost certainly in a pit below ground level. The target frames installed in the pit were probably ‘Ralston Dual Canvas Frames’ (image above), produced in Glasgow. When visiting the range, clearly identifiable metal components, once part of such frames, still protruded from the soil along with cogs. The maps do not show any protective earth bank (mantlet) in front of ‘Targets’. This supports my suggestion that the target frames were erected in a pit some 7 feet below ground level, with only the canvas targets, when raised, visible above ground level. ‘Markers’ were positioned safely within the pit to operate and mark/patch the targets and indicate the score. Could it be the case that some years later the range was ‘modernised’ by simply filling in the pit, while leaving the redundant target frames in situ, which then led to some parts of the structures still jutting out of the ground?

Part of the range upgrade would have been the construction of a wall to support the mantlet, to which a roof once was attached (now demolished for reasons of safety – see below). The space behind the protection of the wall, often referred to as ‘markers’ gallery’, allowed markers to be positioned to operate, mark and repair the targets. The wall was necessary as a different type of target frames, now erected above ground level, had come into use. The targets now in use are likely to have been mounted on ‘Windmill Target Frames’ (Image above), consisting of substantial wooden vertical post, which supported an axle, around which the targets, mounted on a wooden frame, would rotate.

I have no evidence for this, but it seems possible that the range was ‘modernised’ in connection with the drastically increased need of more rifle range capacity during WW1. The new linear mantlet would have allowed the erection of at least four Windmill Frames.

Bill Flentje 2019

The Target Today

As part of the Higher Level Stewardship Scheme it was identified that the degrading rifle target was a danger to livestock and visitors to the site and it was decided that the collapsing lean-to roof should be removed. As well as this, the marker’s hut, used to identify if riflemen had hit their target, was also identified as being in a poor state of repair and the decision was made to undertake conservation works on this brick structure.

Before these works were undertaken, the scheme felt that it was important to record the site in high detail so that archaeologists and historians in the future could refer back to how the rifle target was constructed before it was partially demolished. To do this, archaeologists from the New Forest National Park Authority and the University of Southampton undertook a terrestrial laser scan survey of the site and its surroundings.

This high-tech, high-definition approach helped to record the structure to centimetre accuracy in three dimension and will allow researchers to measure, analyse or even re-construct a replica of this structure in the future.

This animation was created with the help of Archaeovision using the data recorded by the terrestrial laser scanning survey, and provides the viewer with a fly through of the site before the roof was removed.

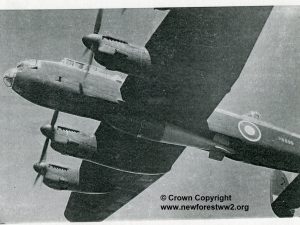

Napoleonic Rifle Ranges – History Hit Film

This short clip provides a bit more history about some of the Napoleonic rifle ranges that can be found across the New Forest.