Memories of a Rifleman

Rifleman Robert J G Comber

Queen’s Own Rifles of Canada, R.C.I.C.

Spring 1944, I was located in Boscombe, Hampshire. I was a Bren Carrier driver, and every day I worked on my machine along with all the other men who would be with me in the days to come.We took special pride in our equipment for we knew that one day soon they would be a means of strength preservation.

April 1, 1944 we moved from Boscombe Gardens to the open country north of Southampton in a small place called Chilworth Manor. Here the rifle companies carried out rigid drill and P.T. With their nets and ropes they’d go scurrying off through the trees like the monkeys in a jungle. Or perhaps they would suddenly pop up out of a hedgerow beside you or go wriggling off down a ditch like a lizard, to pop up further down and make an organized charge on bayonet dummies. To see these fierce organized charges made one feel full of pride, as they were good. One could see that all this training had a clear purpose behind it. One day they would bring honour and freedom to their own and other peoples of the world. About this time orders came to take all the Bren Carriers away to be waterproofed at Gosport. There the first fittings were attached.

April 25, 1944 from Gosport we went to a secret rendezvous north of Romsey.

Our new home was a huge forest. On entering one could not help admiring the magnificent beauty of the flowers and ferns that were just awakening from their winter’s sleep. The cry of a hen pheasant disturbed from her nest, the chattering of gray squirrels peering through the bracken, the caw of the rooks building their nests in the tall oaks. This was a place of secluded peacefulness. All too soon we realized that it was too good to last.

High above us in the blue was a tiny silver thread, the vapour trail of a German plane eight miles up. This was one time that his camera must not detect the scene below him. If such evidence was placed in the hands of our enemies hundreds of planes would fly over this night and hurl tons of destruction on the mechanical might of our invasion forces. Such a disaster must never happen. The siren sounded and a deadly silence settled down on that shielding forest.

No sound or movement betrayed us. Even the wild creatures seemed to sense the impending results of detection. Slowly the ominous distant hum trailed its feathery wake across the sky, alone and undisturbed. He was too high to be shot down, far above the range of our ack ack guns. Camouflage was our only safety. In that we placed our entire confidence.

Suddenly, the woods were pierced with the shrill, nerve racking wail of the ‘All Clear’. Once more it was safe to move about and carry on with the important work that was far from finished.

May 1944, On locating a large hollow covered with trees we immediately began to build a small shelter. Taking a Bren Carrier tarpaulin we stretched it around a tree leaving an opening for a door. By nightfall we were fairly comfortable, complete with homemade wooden beds, an outdoor stove, well covered so that we could use it during the blackout hours. We were to be a self-contained unit of six men, doing our own cooking and our own guards.

During the next day we searched the woods for a suitable place to carry out our waterproofing operations. We chose an unused gravel pit large enough to accommodate 10 or 12 carriers and suitable camouflaged with overhanging trees. By breaking down one side of the gravel face we made a ramp-way. From this ramp we could run the finished vehicles deep into the woods under the finest natural cover. The giant beech and oaks shut out the sun all day. Here the carriers would stay until time to move to destination unknown.

It was best to work at night so that the equipment we used did not reflect the light from the sun. In a tiny bay in one corner the waterproofing kits were piled, ready for immediate use.

During the small hours of morning we were awakened by the whine and rumble of the carriers coming in. Destiny had begun its slow but steady approach. In hundreds of similar places the great machine of war had meshed its gears and slid into motion. Day and night the woods resounded to the clatter of tools on steel and clank of tracks. The carriers were drawn up ahead of the rest and they were rapidly being dismantled. A passing stranger might have thought that we were taking them apart. The reason for this was to make sure that not one part missed a good portion of waterproofing substance.

Slowly, but surely the work forged ahead, the water tight seams of bostic and asbestos compound crept through the hulls, proofing them against the sea that would pour over them on that eventful day. Each crew completed one carrier per day and this went on seven days a week.

During the short evenings we would slink off into the fields and hedges with rifles and poach an unwary pheasant or rabbit. This would make an appetising addition to our rations. With the twilight we would sit around our fire and talk of home and our escapades in civilian life. These were mild compared to some of the wild times in the army. Home was the most talked of subject. Letters home were censored so it was impossible to give the folks the least idea of what was going on. Exciting games of dice and cards were our main source of pleasure.

My closest pal Bill (William Cuthbertson Calbert) had not seen his new English wife for a long time, so he decided he would steal away home for a few hours. This was a breach of regulations that called for severe punishment.

Never-the-less he went to see his wife one last time before being called away. While he was gone I kept a watch on both our carriers. All the while he was gone I complained about him leaving me to this task. It was not long after that though I was glad that I had let him go. That was the last time he was to see his wife, Alice.

5 June, orders came down to proceed with the invasion.

6 June 1944, heading for the beach at Beny-Sur-Mer.

As Bill and his crew left the barge in their carrier on 6 June heading for the beach at Beny-Sur-Mer they fouled a sea mine and became a blinding ball of flames and twisted steel sizzling in the sea. It was a hard thing for me to watch from shore. Only then did I realise what was taking place around me. The wreckage was vast and startling, the terrible waste and destruction of war, and loss of human life. Anything and everything became expendable.

You can find out more about the New Forest’s vital role in D-Day from Mulberry Harbour, to holding camps, road widening, advanced landing grounds, PLUTO and Embarkation by visiting our main page on D-Day in the New Forest.

CALBERT, WILLIAM CUTHBERTSON

Age: 22

Date of Birth: 18 Aug 1921

Date of Death: 06 Jun 1944

Rank: Rifleman

Unit: Queen’s Own Rifles of Canada, R.C.I.C.

Force: Army

Service Number: B66122

Reference: RG 24

Volume: 25517

Extra Information: Son of William Cuthbertson Calbert and Annie Calbert; husband of Mary Alice Calbert, of Locust Hill, Ontario.

Grave Reference: I. B. 11.

Cemetery: BENY-SUR-MER CANADIAN WAR CEMETERY, REVIERS

On 23 July I was wounded by friendly fire one mile from Falaise, France. I was taken back to continue my contributions to the war effort.

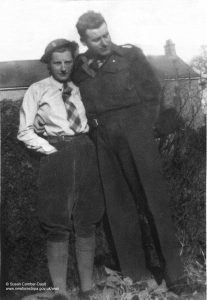

On 24 November I met, Freda Sque, who was in the Women’s Land Army on New Park Farm in Brockenhurst, Hampshire, we fell in love and were married 20 June 1945 in Brockenhurst.

© Susan Comber-Dault