New Forest Salterns – An Overview

From at least the late Bronze Age onwards, the flat coastal areas of the New Forest have been important for the sea-salt industry that flourished until the middle of the 19th century, resulting in large saltern complexes and large areas of the coastal marsh landscape surviving today.

Salt has always been an important commodity, and not just for culinary purposes – it was also used as part of the tanning process, and before the invention of fridges and freezers, as a preservative. Since at least the Iron Age, salt was extracted from sea-water by evaporation at places along the New Forest coast. Salt would then be carried inland across the New Forest to settlements using donkeys or packhorses along well-worn routes.

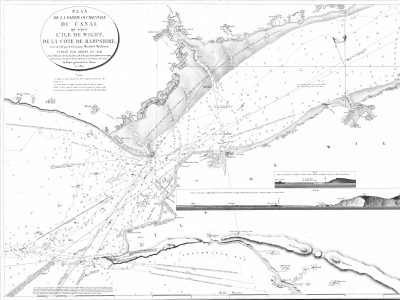

During the 1700’s Lymington and the New Forest coast became the centre of salt production on the south coast following an industrial approach to producing salt, making use of the flat coastline and double tides. A continuous line of salt works occupied the 5 miles of coastline from Lymington to Hurst Spit as well as large areas of the Beaulieu River bank and Southampton Water shore. By the late 18th century, there were 149 salt pans functioning along the Solent. These mainly consisted of large areas of evaporation ponds, wind pumps to move the concentrated saline solution to coal fired boiling houses containing metal pans to complete the process of making the salt crystals.

The sea salt manufacture in the New Forest was seasonal, depending on good weather, but on average the season was sixteen weeks. Each salt pan in a boiling house would produce about 3 tons a week and Lymington supplied most of Southern England with salt and also exported large quantities to the Newfoundland fisheries and other areas.

Salt became an easy target for heavy taxation; in 1755, £57,891 worth of tax was collected, showing how large and important the industry was to the area. However by the end of the 18th century the rising taxes, coupled with a few bad seasons and the arrival of better transport making the cheaper mined salt from Cheshire easier to supply saw the rapid decline of the Solent salt pans. The last salt house closed in 1865 and within a few years the boiling houses were removed and the salt-ponds filled up and levelled off for grazing. Two buildings survive from this industry in Lymington and the landscape designed to flood has become famous as a wading bird nature reserve.

You can find out more about specific Salterns and the New Forest salt industry in the following articles:

Salterns

New Forest Salt Industry and Heritage