Castle Hill – Adulterine Castle

Just north of the scheduled Iron Age hill fort of Frankenbury lies another outcrop of higher ground with some earthwork banks. The area is known as Castle Hill, which provides a potential clue into what can be found here. The site is recorded in the Hampshire Historic Environment Record as A ringwork and bailey castle of three wards dating to the Medieval period, possibly built on the site of an Iron Age promontory hillfort.

What survives:

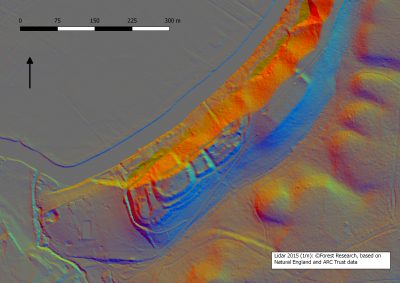

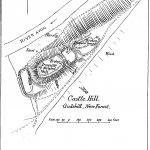

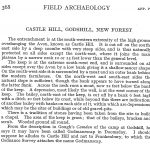

Three earthwork ‘wards’ along a ridge, beside the river Avon. The inner ward resembles a weakly banked partial ringwork with 2 outer baileys. The ringwork is the SW most of the 3 parts and measures 85m (SW-NE) and 57.5m (SE-NW). The middle bailey measures 37.5m (SW-NE) by 60m (SE-NW). The NE most part of the earthwork is less complete but measures at least 55m (SW-NE) and 47.5m (SE-NW). The earthworks survive fairly well except for the NE most bailey which is heavily damaged by quarrying. As you can see from the Lidar image it is an unusual earthwork comprising an oval ringwork with two small square outer baileys to the NE. It has been interpreted as an adulterine castle, perhaps the temporary fortification used by Hugh de Puiset in 1148.

Adultrine Castles were mostly built during the civil war of the Anarchy (1135 and 1153), fought between the factions of Stephen of England and the Empress Matilda. This was a succession crisis: Henry I’s legitimate son William died in 1120, he tried to install his daughter Matilda, but on his death in 1135, his nephew Stephen of Blois seized the throne, which resulted in lots of fighting with barons and in 1139 Matilda invaded with her half-brother Robert of Gloucester. No side was victorious, and in 1148 Matilda left the country and campaigning passed to her son Henry. In 1153 Stephen and Henry negotiated peace at Winchester and Henry became Stephen’s heir. Stephen died shortly after and Henry II was crowned

Both sides built a number of new castles to defend their territories and act as bases for expansion, typically motte (raised earthwork) and bailey (enclosed courtyard) designs. Many of these castles were termed “adulterine”, meaning unauthorised, because no formal permission was given for their construction.

Traditionally the King retained the right to approve new castle construction, but in the chaos of the war this was no longer the case. Contemporary chroniclers saw this as a matter of concern; Robert of Torigny suggested that as many as 1,115 such castles had been built during the conflict, though elsewhere he also suggests an alternative figure of 126.

Matilda’s son Henry II assumed the throne at the end of the war and immediately announced his intention to eliminate the adulterine castles that had sprung up during the war, but it is unclear how successful this effort was; recent studies of selected regions have suggested that fewer castles were probably destroyed than once thought and that many may simply have been abandoned at the end of the conflict. Certainly many of the new castles were transitory in nature: historian Oliver Creighton observes that 56 percent of those castles known to have been built during Stephen’s reign have “entirely vanished”.

The site is recorded and illustrated in J P Williams-Freeman (1915), Field Archaeology as Illustrated by Hampshire.